Fragments of War

Photographs by Dmytro Kupriyan (Ukraine)

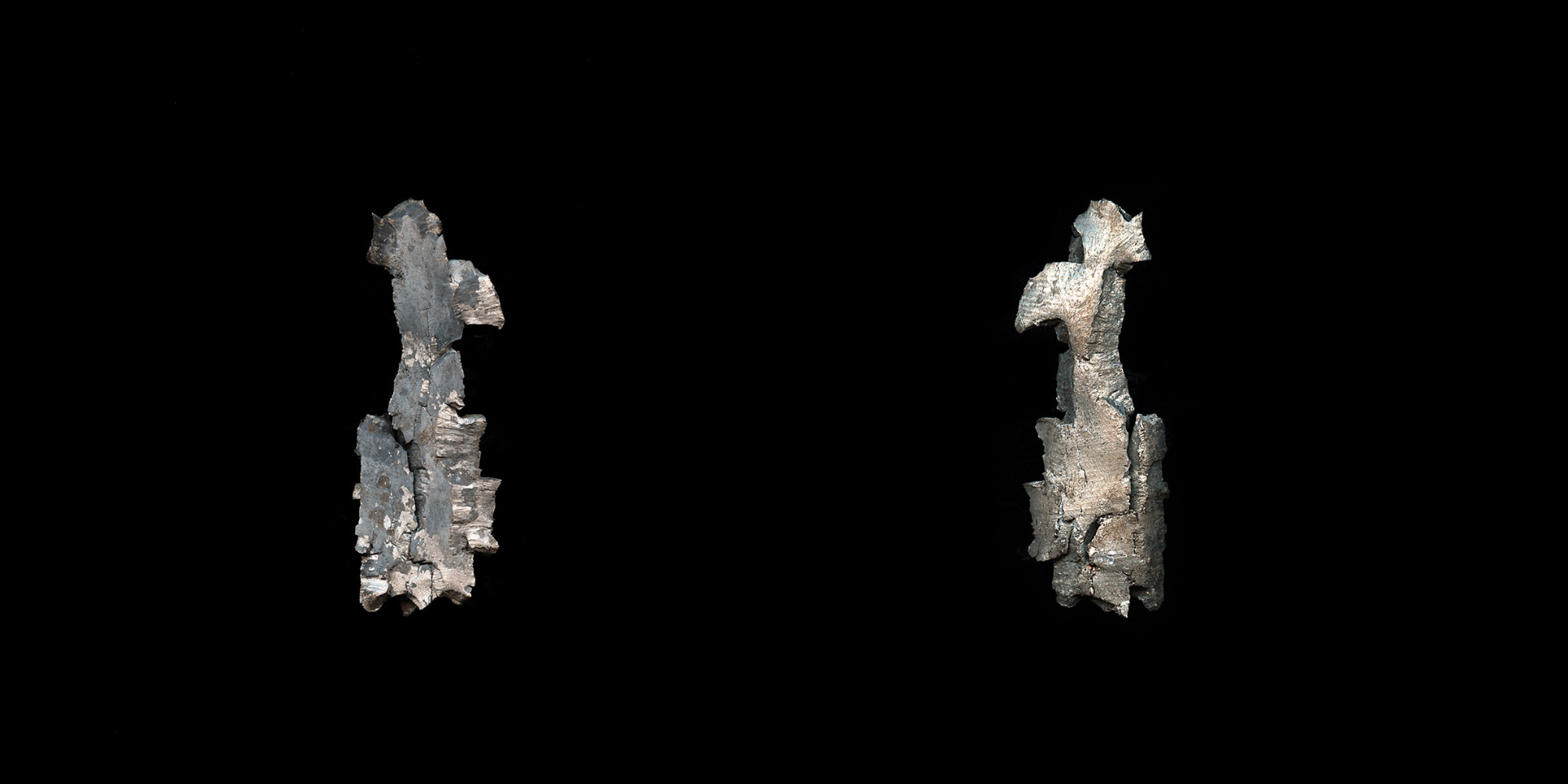

“Life size scans of munition fragments found in the territory of the Donbas, Ukraine, look like asteroid parts with grooves and bends, whose sharp edges can easily kill or maim anyone on their way from the barrel to the place of impact and spalling.

Each fragment has its own history, the circumstances in which I found it; origin, where it came from and how I came by it; place where it was found. We will probably never know which side of the conflict has created it, but after the spalling and impact begins another story – a story related to the places, situations, people who were nearby and saw the horror of the war.

And now, collecting these fragments piece by piece and compiling a new history which describes what happened during the war, the participation of the people, soldiers, volunteers, citizens – everyone became a fragment that was knocked from his/her place in life and abandoned on the battlefield and up to pile into something new and powerful.”

This is what Ukrainian photographer Dmytro Kupriyan, born in Kyiv in 1982, writes about this photo work. It was taken during his missions in 2015 and 2017 as a volunteer, as a photojournalist and as a soldier on the front line in the war against the separatists in eastern Ukraine.

Kupriyan uses photography to present his view of society’s problems in a simple, minimalist and elegant way, as well as to point out ways to solve them. In his early project “Tortured”, he portrayed 65 victims of torture by the Ukrainian police. In “Fragments of War”, he deals concretely with the war in eastern Ukraine, which has been going on since 2014. In a photographic work “When the War is over”, Kupriyan looks at the future and the aftermath of any conflict to show ways to end the war and define what will be after the war. Kupriyan sees “the only way to solve the problems and misunderstandings in societies is the dialog in all meaning of it: verbal, subverbal, physical, etc.”, as he articulated in a statement. The events of the last few weeks, Russia’s open war against Ukraine, abruptly broke off the dialogue. Dmytro Kupriyan is currently serving again as a soldier in the Ukrainian army. This exhibition was created in cooperation with eastFOTOgallery in Grünewald. We thank Jürgen Roloff for arranging it and for managing to reach Dmytro at short notice under the current circumstances in order to authorise the exhibition.

The events of the last few weeks, Russia’s open war against Ukraine, abruptly broke off the dialogue. Dmytro Kupriyan is currently serving again as a soldier in the Ukrainian army. This exhibition was created in cooperation with eastFOTOgallery in Grünewald. We thank Jürgen Roloff for arranging it and for managing to reach Dmytro at short notice under the current circumstances in order to authorise the exhibition.

Photographs: Dmytro Kupriyan

Curation: Jan Oelker

Digital conversion: Simon Wolf, Aimée Deutschmann

Texts: Dmytro Kupriyan, Jan Oelker

Proofreading: Christin Finger

A digital supplement to the exhibition “Dmytro Kupriyan – Fragments of War” (15.03. – 06.04.2022) at the Galerie nEUROPA

fragment # 1

Found in the town of Shchastya in Novoaydar district, Oblast Lugansk.

Weight – 1.9 gram

VOG-17 (automatic grenade launcher)

Number of fragments – about 100 pieces

Destruction area – 70 square metres

Calibre – 30 millimetres

Cartridge length – 132 millimetres

Grenade length – 113 millimetres

Grenade weight – 0.35 kilograms

Weight of shell – 0.28 kilograms

Grenade initial velocity – 185 metres per second

MaMaximum shooting range – 1700 metres

The town of Shchastya in the Novoajdar district of Ukraine’s Lugansk oblast became a frontline area. As part of a group of journalists I came to photograph the life of the inhabitants. People were adapting to the new conditions, the place was alive, or at least they were trying to live a regular life, in spite of the frequent shelling in the outskirts. Some of the shells hit the houses in the village.

On the second day of our stay, we interviewed the chairman of the village council – he told us about the changes that had taken place – when he received a call that there had been a grenade impact nearby and a civilian had been wounded. A VOG-17 mortar shell flew through the open door of a shop and exploded on the floor. A young man suffered an abdominal injury. His mother was letting her emotions out cursing the war. The doors were facing the separatist side but they are afraid to call them guilty or to call them enemies, just as they are afraid to call the Ukrainian military defenders. And just as well as they are afraid to call this war a war.

fragment #2

Found in village Piski of Yasynuvata Raion, Oblast Donetsk.

Weight – 71.6 gram

Mortar shell 120 millimetres

Calibre – 120 millimetres

Fragments starting speed – 1800 metres Destruction area – 1290 square metres

Weight of shell – 16 kilograms

Weight of the explosive – 2.6 kilograms

MMaximum shooting range – 7.1 kilometres

Mine starting speed – 272 kilometres per hour

Something whistled overhead. A mortar shell! Fractions of a second to make a decision. Only one solution – to drop down. And then crawl away. Boom! Fragments covered the nearby trees and roofs, smashing into the walls, falling into the snow. I crawled into a hole under the cannon heel where a fighter was already hiding. The space was crowded.

One more whistling and another explosion. Then another one. I took photos of one guy in front of me; another got up from a pit next to me.

– Send me a pictures?

– Yes!

This time no one was killed or wounded. Mortar rounds are are common here, and the daily duels mean that the village has only one intact house left, the walls are shredded by the fragments, wounded dogs wandering the streets, almost all the inhabitants have left the village and the place has become a ghost town.

Journalists rarely reach the village of Piski, only the most daring ones. And only a few had gone further to Donetsk airport. Six weeks later, on 28 February 2015, photographer Sergei Nikolayev was killed here by a mortar fragment.

fragment #3

Found in the village of Piski in the Jasinuvata district, Oblast Donetsk.

Weight – 46.3 gram

Mortar shell mine 82 millimetre

Calibre – 82 millimetre

Number of fragments – 400-600 pieces

Destruction area – 715 square metres

Weight of shell – 3.31 kilograms

Weight of explosive – 0.4 kilograms

Maximum shooting range – 3.9 kilometres

“Jazz Band” mortar position of Ukrainian Volunteer Corps Right Sector in the village of Piski in the Donetsk region.

A squad goes out for a 24-hour mission. I had persuaded the commander El Gato (Spanish for cat) to take me along so I could take pictures.

First the position is prepared, the mortar shells are checked and cleared of snow and dirt (a job done by the newcomers who learn from the more experienced – they have to start with something), and then they are equipped with gunpowder and detonators. El Gato had called his commander several times asking for more mortar shells. The commander promised, but the military is not allowed to share weapons with the Ukrainian volunteer corps Right Sector, as it is not officially recognised and is basically an “armed formation” that does not report to anybody. Therefore, mortar shells are scarce and used very carefully, only when the results are certain:

– There is something “warm” moving in the foliage – comes a message from the NEBO (sky) position, which has the whole village of Piski in its sights, – throw a fougasse there. – Negative, mortar shells are scarce, keep watching, – replies “Jazz Band”.

After a while, the radio is active again:

– Vehicle headlights behind the dump, shoot a “lighter” shell there, pretty please.

– Shell gone, watch it, – reports “Jazz Band” immediately after the shot, getting thanks and good night wishes in response, just to be woken up to be set a new target in a while. At night the fighters jumped up on alert and, as routinely as going to work, promptly grabbed the rounds and rushed to the mortar where others were already setting it up.

Several times the other side responded with mortar shells, but they didn’t even come close…. They fired at random.

So the day and night passed, and in the morning a new day shift came, and casually the duty was handed over to the next squad, and we dragged ourselves through the village to a more or less safe basement to get some sleep.

fragment #4

Found in the village of Debalzewe, Oblast Donetsk.

Weight – 196,7 grams

Artillery shell, probably 152 millimetres

Calibre – 152.4 millimetres

Weight of shell – 43.56 kilograms

Weight of the explosive – 7.65 kilograms

Starting shell speed – 810 metres per second

Starting fragments speed – 1800 metres per second

Destruction area – 950 square metres

Maximum shooting range from howitzer 2A18 (D-30) – 17.4 kilometres

Number of fragments less than 1 gram – 700 pieces

Number of fragments 1 to 4 grams – 1160 pieces

Number of fragments weighing more than 4 grams – 1600 pieces

At the end of January 2015, heavy fighting broke out around Debaltseve, leading to the Debaltseve pocket. The troops were in danger of being completely encircled and there was a feeling of an imminent end-all.

At that time, the fourth wave of mobilisation began and I was called up. I first had one month of training, then the actual military service began.

The officers read out the news and announcements during and between the lectures. All our thoughts were there, everyone was excited and hoping to be sent to such an uncertain and illusive front.

My time in the service turned out to be away in the deep rear in a communication unit and I had not been rotated to take part in the activities at the front.

These shell fragments were lying on the floor of an office in our military base, abandoned and forgotten, and would have ended up in the rubbish at some point. They came from Debaltseve along with the army’s retreat under massive shelling, brought by officers as souvenirs. The equipment that came back was hit and mutilated, with fragments that had pierced the aluminium truck shelters, and some cars had been burnt or left behind in Debaltseve.

If I haIf I did not get called in to serve in the Armed Forces I would have definitely been in Debaltseve taking pictures. Either way, I ended up with these fragments.

fragment #5

Found in the town-like settlement of Stanizja Luganska, Lugansk region.

Weight – 135.3 gram

MLRS GRAD (BM-21) rocket shell

Calibre – 122 millimetres

Maximum shooting range – 20100 metres

Destruction area – 1000 square metres

Weight of shell – 66.6 kilograms

Number of prepared fragments (weight 2.4 grams) – 1640 pieces

Number of fragments from shell (average weight 2.9 grams) – 2280 pieces

There was shelling the day before. The checkpoint was shelled by MLRS Grad (BM-21) rocket launchers, resulting in many dead and wounded and damaged equipment – they collected everything that was left and redeploying to a new location. As we were prohibited to take photographs at the checkpoint, we took what was left of a destroyed car service station on the side of the road. We walked around and saw what happens when a building is hit directly by a missile – the roof is torn away, the floors are broken or simply fell in inside, the doors are blown away or inflated like tin, window glass is blown outwards, thin walls are pierced by shrapnel, with everyone inside most probably dead.

I found this fragment under my feet on the street.

At the moment cars are not allowed to pass, the road is closed and we cannot go back. After several days near the front line, it is time for us to return, but we are forced to stay. Soon the checkpoint was cleared and traffic resumed, allowing us to go on.

Six months later, I had the opportunity to feel and see the shelling by an MLRS Grad (BM-21) at close range, from a post next to the one that was fired on – it was friendly fire that hit a building in the village of Piski in Donetsk oblast, the basement of which was occupied by soldiers of the Ukrainian Volunteer Corps Right Sector.

fragment #6

Found in the city of Debaltseve, Oblast Donetsk.

Weight – 134 gram

Artillery shell, probably 122 millimetre

Calibre – 122 millimetre

Weight of shell – 21.76 kilograms

Starting shell speed – 690 metres per second

Starting fragments speed – 800 metres per second

Destruction area – 800 square metres

Maximum shooting range from howitzer 2A18 (D-30) – 15.2 kilometres

Number of fragments from 1 to 4 grams – 1000 – 1500 pieces

Number of fragments weighing more than 4 grams – 400 – 850 pieces

It is rare to see transports or anything on wheels leaving the village of Piski in Donetsk oblast from the front line. The last one was the one that brought me and left the next day, a week ago. It was an armoured SUV belonging to Commander Chornyi (Black), who was at the wheel. The car was heavy and we skidded off the road several times.

It was already time for me to return home to “the mainland”. My mother called me several times:

– Where are you? – was her usual question…

In the ATO area, – was my also usual reply so as not to unmask location.

– Are you taking pictures ?

– Taking… – not very informative as to what exactly I was doing.

Departure day. The backpacks were packed into an ancient, bright yellow shiguli with a huge flag attached to its luggage rack. Surprisingly for this area, the car still had all the windows intact. This means that the trip will be comfortable.

Three people were leaving, including me…. We went to say goodbye to the soldiers, but even before we moved away from the car, there were two explosions nearby. A brick wall ten metres away from us was hit and flew apart brick by brick. We fell into the snow and crawled under the car. Second salvo – two explosions … We jumped up and ran into the basement. As soon as we jumped down the stairs, a blast behind us threw another soldier in sending him into the ceiling.

Everyone is alive. The kitchen no longer exists. The shelling ended as abruptly as it had begun.

We quickly jumped into the car and headed towards to leave…

I don’t know why, but no one was hurt that day, the impact just missed the target. Chance…

fragment #7

Found in the city Debalzewe, Oblast Donezk.

Weight – 23.9 gram

Artillery shell, probably 122 millimetres

Calibre – 122 millimetre

Weight of shell – 21.76 kilograms

Starting shell speed – 690 metres per second

Starting fragments speed – 800 metres per second

Destruction area – 800 square metres

Maximum shooting range from howitzer 2A18 (D-30) – 15.2 kilometres

Number of fragments from 1 to 4 grams – 1000 – 1500 pieces

Number of fragments weighing more than 4 grams – 400 – 850 pieces

It has been three days since we left Kyiv with a vehicle to deliver voluntary aid to the soldiers on the front line, and also we need to pick up more cargo on the ground and deliver it to the front line as well.

The plan we had was not too precise or detailed – we were to deliver warm clothes to friends in the village of Piski and then continue via Kramatorsk and Slowiansk to our friends in Volnovakha and to our volunteer friends we had met through social networks in Mariupol. I visited the city three times and didn’t have much to show for it – as a journalist I couldn’t take pictures of military operations at the front, as I was either told I was too late or not allowed to take pictures…

The day before we arrived in Mariupol, the soldiers of the Donbas volunteer battalion came under fire and suffered casualties. The shelling took place during another truce, but everyone kept quiet about it… We were immediately told the reason – it was a reaction to accurate shelling by Ukrainian artillery. A direct hit on a training camp or base that killed about 200 terrorists, so both sides used artillery during the truce. About a week later, it was reported in the news and another unit took credit.

In another town on the front line, a military mortar unit was in an abandoned school yard and from 3 to 4 p.m. they took turns shelling the areas on the other side of the front line. There was no return fire because the other side knew where they were firing. If they had fired back, the mortars would simply have been moved to another position, changing the time and order of the attacks…. It suited both parties.

Not everything that happens at the front finds its way into the news and becomes known to the public. Many human relations remain unknown and especially ‘relations’ across the front as mentioned above…

fragment #8

Found at the base of the UVC RS (Ukrainian Volunteer Corps, Right Sector), Oblast Donetsk.

Bullet 5.45 millimetre

Calibre – 5.45 millimetre

Diameter – 5.60 millimetres

Length – 25.5 millimetres

Weight – 3.5 grams

Starting speed – 915 metres per second

FSighting range shot from AK-74 – 600 metres

Bullet 9 millimetre

Calibre – 9 millimetres

Diameter – 9.27 millimetres

Length – 11.1 millimetres

Weight – 6.2 grams

LStarting speed – 315 to 420 metres per second

Sighting range shot from PM (Makarov pistol) – 50 metres

The war was in full swing, the capture of Ilowaisk had just taken place, everyone was focused on helping and volunteering at the front.

Numerous volunteer battalions and military formations were organised. They were already armed and took their places at the sections of the front.

As a driver, I took cameraman Leonid Kantor to shoot a film about one of these battalions – the Ukrainian volunteer corps Right Sector, which later turned out to be the best organised and most militant battalion I have ever seen. Right Sector became a bogeyman for the other side of the front line, used to frighten as if they were savages ruthlessly destroying their enemies.

I didn’t go to the front, but stayed at the base. I did a one-week training course on weapons handling, combat training, assault and sabotage training, navigation – basically the things soldiers should be taught in the army. I collected the shells and bullets on the firing range and made the collages.

There I met soldiers who later became famous for fighting in the village of Piski – they were resting and waiting for relief. Young replacements arrived, most of whom were sorted out on the spot, and the rest were sent to a checkpoint, then to the village of Piski, and – as the highest privilege – to the Donetsk airport, in recognition of the experience they had gained and as a promotion. Those who fought at the airport were called “cyborgs” by the terrorists themselves, and this title will go down in history.

Who was I at this time?

A fighter. A driver. A journalist. A volunteer. A citizen.

fragment #9

Found in the city Debalzewe, Oblast Donezk.

Weight – 91.6; 14.1; 16.1; 31.2; 34.3; 67.4; 16.8 grams (from top to bottom).

Artillery shell, probably 122 millimetres

Calibre – 122 millimetres

Weight of shell – 21.76 kilograms

Starting shell speed – 690 metres per second

Starting fragments speed – 800 metres per second

Destruction area – 800 square metres

Maximum shooting range from howitzer 2A18 (D-30) – 15.2 kilometres

Number of fragments from 1 to 4 grams – 1000 – 1500 pieces

Number of fragments weighing more than 4 grams – 400 – 850 pieces

The beginning of the conflict in eastern Ukraine showed that the army as an institution does not exist in Ukraine and that what does exist is not functional. People started to organise themselves into volunteer battalions and arm themselves, they had a goal and a personal motivation – to protect the integrity of the country. It was the volunteer battalions that were the first to go to the front and start fighting.

As a journalist and volunteer, I have been to numerous battalions fighting in the Donbas, seen people who belonged to them, photographed them and talked to them.

In January 2015, I myself was mobilised and joined the ranks of the Ukrainian armed forces.

I was assigned to communications, although I had completed the course to become a press officer and had tried for six months to get myself transferred to a combat unit at the front in that capacity…. but the press corps proved to be a new institution that did not work as a support. The army never liked change and did not want to work with the press. However, there were people who helped the journalists on their own initiative and with the support of the commanding officers.

A year later, at the end of my service, when the army had almost taken shape, the war in the Donbas became a frozen conflict, similar to Moldova’s Transnistria and Georgia’s South Ossetia, with the corresponding consequences, and no one knows what will become of it in the future.

fragment #10

Found in the town-like settlement of Stanizja Luganska, Lugansk region.

Weight – 4.2 gram

Heavy machine gun bullet BZ-A

Calibre – 23 millimetre

Bullet weight – 175 grams

Starting fragments speed – 900 metres per Maximum shooting range of ZU-23 – 2000 metres

This war has taken a lot of colourful and interesting people under its wing – people who gave up their jobs and answered the call to join volunteer battalions to defend their country. Why did they join? First and foremost, because the majority of Ukrainians have realised that sitting it out is not their thing.

– 1 –

My friend Ivan Havrylko has two children and was able to avoid being called up in August 2014 for this reason alone. In the run-up, he was nicknamed “the geologist” because he worked as a geodesist in civilian life. We met in the summer of 2007 when we crossed the Black Sea to Georgia and back by boat. We were young and passionate, real Cossacks. Ivan did indeed look like a Cossack – tall and strong, with a curl of hair on his head – everyone liked him right away.

On the eve of the 2015 New Year holidays, I visited him at the front line in the village of Karlivka near the notorious village of Piski on the outskirts of Donetsk. It was quiet there at the time, the village was away from the front line; only the so-called avatars (drunken soldiers) complained about us from time to time. The position was gradually established, bunkers were dug and isolated; the checkpoint worked and allowed traffic and people to pass in both directions. Ivan went on duty at the checkpoint.

– 2 –

Our route for the next few days in the ATO area took us through the villages of Stanizja Luganska and Novoajdar, Shchastya and Trochisbenka. I rode in the car of Lugansk human rights activist Kostiantyn Reutskyi together with two other journalists. We wanted to shoot a reportage about civilian life against the background of the six-month war in Ukraine. Reutskyi was acting as a reporter and cameraman at the time – shooting and doing stand-ups, providing commentary and interviewing officials, military personnel, teachers and civilians. Before that, he was looking for ways to communicate with separatists holed up in the security service building in his hometown of Lugansk, but soon had to leave the city because of threats. He still believes that he will return to his hometown, that his family will return, but he has already started a new life in Kyiv.

– 3 –

After shooting “War at his own expense”, activist and filmmaker Leonid Kantor started shooting his second film “The Ukrainians” – for which he went to the Donetsk airport where fierce fighting was going on and where all the news was coming from at the end of September 2014. But the aim of the fighting around this remote outpost was incomprehensible to everyone; it was just a place where the armed forces of two countries measured each other. Leonid left his family and farm in Obirok for a while to document and film the fighters of the Ukrainian volunteer battalion “Right Sector” defending the airport and the nearby village of Piski, to show the whole world – which at that time only got to see an endless stream of Russian propaganda – that Ukrainians are ready to fight against this powerful and formidable military machine, no matter how scary it may seem.

– 4 –

Trochisbenka is a village on the front line. It is frequently shelled by the separatists across the river, as the armed forces and the Aidar battalion are on the outskirts of the village. There are frequent power cuts and the residents were living in the basements where, on top of that, the gas had been turned off…. We filmed our report and returned, encountering several armoured military vehicles approaching us. We continued on, but after a few turns we seemed to get lost, so we asked the military men, who were discussing something in the middle of the dirt road in their old UAS SUV, for directions. It turned out that they were policemen from the Novoajdar police department of the Lugansk region who were patrolling the area on their own. After a short conversation, we were invited to visit them and spend the night with them…. Their leader and head of the group was Leonid Pantykin, who six months ago was deputy head of a police station in Lugansk and who had managed to get about 500 children out of the occupied territories after the separatists captured the city, and now he was head of the Novoajdar police department.

– 5 –

Once again I find myself in Mariupol. I wanted to take in something on the front line approaching the city and the preparations for its defence, so I was prepared to stay there for a long time and perhaps find myself on the other side of the conflict should the city be captured. During the street fighting, the police station and the city administration buildings came under fire and were still damaged. The Red Cross was distributing aid to refugees nearby, there were roadblocks and homes that would be shelled by separatist rockets a few months later. I photographed life in the town, the aftermath and the reactions of the residents. During this time I met a German who came with his own car to “end the war”, as he explained it. In some ways he was mad and angry, in others he was just lucky – he talked to Vitali Klitschko’s wife and explained to her how to stop the war, devised strange formulas like “√RATIO = LOVE” and planned to go to the president and separatist leaders to persuade them to stop.

I was afraid to leave him alone in the city, because he was as naive as a child. He wanted to go to the hospital and give the food he had received from caring people on his long journey to the wounded soldiers, so we joined forces, because actually I wanted to visit the hospital myself. There were some lightly wounded there, while all the seriously wounded had been taken to Dnipropetrovsk the day before. The German handed out various goodies and for some reason also colouring books for children. He was a strange man who somehow combined hatred of war with love of people, and ideas of a global conspiracy with the evilness of individuals, especially Russian President Putin. He saw this war as a struggle between good and evil, and in each individual. We took a photo together in a photo booth and then went our separate ways – he moved on and I decided to return to Kiev.

fragment #11

Found in the city Slowjansk, Oblast Donezk.

Weight – 11.9; 6.4; 9.5; 6.8; 7.0 grams

Artillery shell, probably 122 millimetres

Calibre – 122 millimetres

Weight of shell – 21.76 kilograms

Starting shell speed – 690 metres per Starting fragments speed – 800 metres per second

Destruction area – 800 square metres

Maximum shooting range from howitzer 2A18 (D-30) – 15.2 kilometres

Number of fragments from 1 to 4 grams – 1000 – 1500 pieces

Number of fragments weighing more than 4 grams – 400 – 850 pieces

AnAnd now, two years after, I came back to the so-called Anti-Terrorist Operation area to make a new project about this war and our involvement in it. With my friend Maxim Dondyuk, we drove from Slavyansk to Stanitsya Luganska along the front line, then back to Slavyansk, from where we drove south to Mariupol and back home via Slavyansk. Maxim is doing his project about the war and the scars it leaves, and I’m doing mine called “When the war is over”, about Ukraine’s highest goals, which we lost along the way: the integrity of the country, the restoration of borders and the unity of society against aggression. The war is now in its third year and it is unclear when it will end, just as it is unclear when and where it started. Society gets entangled in the war and treats it as the norm on the fringes of attention. And this illusory loop of time and achievement is the first step towards defeat.

This is the first time I have been to Slowyansk, where the fighting took place – the hospital, the crossroads in front of it and the chemical factory. Since that time, everything has remained untouched, some things began to decay, some things were mutilated by scrap metal seekers with new scars. One of the many houses here has been rebuilt, the bridge that the separatists blew up and the road to it are now rebuilt.

My friend showed me the place where he was when the bombing took place, describing what he imagined then and what he understands now. We went in search of the scars the shelling had left on houses, properties and trees, and climbed into destroyed houses. On the roof of the main hospital building, through a hole where you can see the sky, I found these shell splinters stuck in the beam – with time they have become rusty and hardly recognisable.

The hospital, where many people used to be treated, is now empty and abandoned, so we just walked through the destroyed pavilions and through the garden with the trees scarred by splinters and the moat behind. It looks like the hospital can never be rebuilt, so it is left to further destruction, like a monument for the future, like a warning memorial.

I had the strange feeling that something unusual and unnatural was happening here – it was the silence. People don’t talk about the important things, about their plans, about their citizenship, about their future, as if talking about it wouldn’t happen. People don’t talk about what is bothering them, don’t speak out about the war because they are afraid.

Everything around us is silent, it is a silence like in Chernobyl, where there are no people, but here there are people who are afraid to make the slightest sound, who are afraid to attract attention.

When the war is over

Movie from Dmytro Kupriyan (Ukraine)

“When the war is over” was created in 2017 as a follow-up project to “Fragments of War”. Dmitro Kupriyan deals with the future and the aftermath of every conflict:

“Two civilisations are collapsing in the heart of Europe, and now for the third year, this collapse is being called a war in Ukraine. Ukraine now finds itself between the upper and lower millstones – on one side the Western democratic countries and on the other totalitarian Russia with its territorial claims.

But all wars end, anyway. The main goal of this project is to remind people of the need to end the war and to define what will be after the war. Will be “sunshine” overhead, will it be possible to make a point and move on, because history has shown that everything is relative.”

In 2017, after the ceasefire, Kupriyan photographed in the frontline area in the Donbas, scars and residues left behind by the fighting, as well as destroyed buildings on which the writing “When the war is over” was projected. He accompanies these images with the sound from the car radio, overlapping Ukrainian stations and those of the separatists broadcasting on the same frequency – from today’s perspective, this cacophony seems like a premonition of the media war, which is currently being fought all the more fiercely, just like the fighting with weapons. Both sides broadcast, listening becomes impossible – yet Dmito Kupriyan sees dialogue as the only way to solve the problems and misunderstandings in society.

Dmytro Kupriyan

Dmytro Kupriyan was born in Kyiv, Ukraine, in 1982. He initially studied at the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute and graduated as an engineer, but early on he worked as a photojournalist for news agencies. For several years, he dealt with the subject of torture, especially in the Ukrainian police. He showed his first exhibition on this project “Tortured” in 2009.

With the outbreak of the Ukrainian-Russian conflict in the Donbas, he shifted the focus of his freelance photographic work to the theme of violence in the broadest sense of the word. In his assignments as a volunteer on the front line, during his military service in the Ukrainian Army in 2015 and when he returned to the front line in eastern Ukraine as a photojournalist in 2017, he created various projects about the war in Ukraine, of which “Fragments of War” and “When the War is over” are excerpts in this exhibition.

In recent works he has devoted himself to the need for dialogue in society.

Exhibition in the Galerie nEUROPA

(c) Fotos: Jan Oelker

Gefördert von der Beauftragten der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien